Isabel Salerno

The 2007 film ‘Persepolis’ produced by Marjane Satrapi and Vincent Paronnaud is an adaptation of the 2003 and 2004 autobiographic graphic novels, ‘Persepolis: the Story of a Childhood’ and ‘Persepolis 2: the Story of a Return’. Together, they depict Satrapi’s childhood growing up during the Islamic Revolution in Iran, and her adolescence exiled in Austria and France. This review will critically analyse the film in the context of the Iranian Revolution, how it accurately portrays the inequality between sexes in Iranian society, and how its aesthetics/ cinematic techniques impact the ideas that it communicates.

In 1979, the Iranian Islamic Revolution resulted not only in the fall of the Pahlavi dynasty and its last Shah (King), but also in the creation of a new multi-party republic governed by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. The Pahlavi dynasty was often referred to as a “puppet of the US government” since British and US interests in oil holdings led to an intervention in Iranian political affairs and instigated the previous government under Mohammad Mosaddegh to fall in 1953. In comparison to Mosaddegh’s populist and nationalist Iran, the Pahlavi regime was totalitarian and sultanic. It oppressed and controlled society with the domestic intelligence service, the SAVAK, caused economic crises due to high government spending on elitist institutions, and created high unemployment rates with a low national wage.

Thus, the majority of Iranians wanted change, and a return to Islamic tradition and practice of values since British and US influence on Iran’s governing body had considerably westernised the state. When the new Islamic republic cam to power, the new dictates it introduced dramatically changed the lives of Iranians, most notably women.

Inequality between men and women in the Islamic Republic of Iran

The film centres around the dissolution of the monarchy, emergence of the Islamic revolution in Iran, and its subsequent effects, namely its repercussions for women in its society. This tale of political and social change is told through the eyes of Marjane Satrapi as both a young girl and young woman.

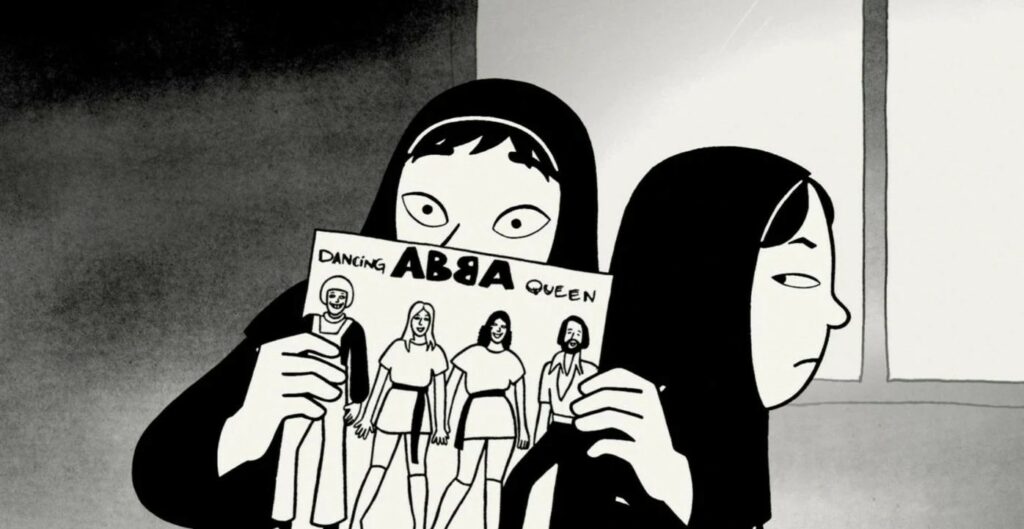

In the film adaptation, Marjane Satrapi’s personal experience of the new Islamic Republic in Iran is first reflected through her change of clothes. When the film begins, the revolutionaries have yet to overthrow the Shah, and Marjane is illustrated wearing somewhat westernised clothing, i.e. a long sleeve tee, a pair of trousers, and trainers. However, the harsh new reality of the traditional Shiite state and its dictates are illustrated 22 minutes later with the image of Marjane and her female classmates all wearing the hijab and black gowns. As we see the cultural shift, we also see that Marjane and her young classmates are not passive to this new dictate and seemingly disregard this symbol (as viewed in the west) of women’s oppression- “[emptying] this signifier of its dominant meaning”.

Following her adolescence in Austria, Marjane returns to Iran and observes how strict the new regime has become, noting that “resistance to state authority no longer happens at a macropolitical level, as seen in the revolution, but at the microlevel”, i.e. in regards to women, wearing minimal makeup and letting some locks of hair loose out of the veil. This in in stark comparison to the men’s clothes that she observes and those women are prohibited from wearing.

As Leigh Gilmore and Elizabeth Marshall observe, “for Satrapi, girlhood becomes a site through which to speak about race, gender, ethnicity, and religion and to teach about social injustice”.

As Naghibi and O’Malley note, the story that Satrapi is telling is universal, thus allowing it to be reflective of many different people’s experiences- i.e. the Iranian diaspora who have experienced the Islamic revolution, and the omnipresence experience of childhood. A story that is told from a child’s perspective could be said to be universal, if one assumes that children are alike everywhere and it is our environment which forms us into adults with diverging values and beliefs. However, it is important to note that Satrapi is not attempting to “universalise human suffering”, she instead uses the narrative of her childhood as a “state through which feminist political critique and self-representation” are expressed.

In relation to her choice to use black and white imagery instead of multicolour, Satrapi remarked that “Black and white makes (violence) more abstract and more interesting”. This of which Ann Cvetkovich observes as a demonstration of “testimony’s power to provide forms of truth that are emotional rather than factual”. Thus, the absence of multicolour imagery forces one to acknowledge the reality of what violence causes, without the distraction of colour elsewhere.

Moreover, the simplicity of the animation ironically “camouflages the complex politics in the narrative”.

Palmer, Lindsay. 2011. “”neither here nor there: the reproductive sphere in transnational feminist cinema”.” Feminist Review (Sage Publications, Ltd.) (99): 113-130. Anderson, Betty S. 2016. ”A History of the Modern Middle East”. Standford, California: Stanford University Press.

Nabizadeh, Golnar. 2016. “”Vision and Precarity in Marjane Satrapi’s “Persepolis””.” ‘Women’s Studies Quarterly’ (The Feminist Press) 44 (1): 152-167. Hajdu, David. 2004. “”Persian Miniatures”.” ‘BookForum’ 32-35.

Cvetkovich, Ann. 2008. “”Drawing the Archive in Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home”.” ‘WSQ’ (1): 111-128.

Naghibi, Nima, and Andrew O’Malley. 2005. “”Estranging the Familiar: ‘East’ and ‘West’ in Satrapi’s Persepolis”.” ‘English Studies in Canada’ 31 (2): 223-247. Nodelman, Perry, and Mavis Reimer. 2002. ”The Pleasures of Children’s Literature”. 3rd. London: Pearson.

Patterson, Eric. 2013. “”Persepolis Film Guide”.” ‘Film Guide’ from Georgetown University. Berkley: Berkely Center for Religion, Peace & World Affairs at Georgetown University, June 1.

Gilmore, Leigh, and Elizabeth Marshall. 2010. “”Girls in Crisis: Rescue and Transnational Feminist Autobiographical Resistance”.” ‘Feminist Studies’ (Feminist Studies, Inc.) 36 (3): 667-690.