Mohamed Aharchi

The conversion of Egypt to Islam came about as a result of the Arab conquest in the early to mid- 7th century AD. While the conquest happened quickly, the religious conversion itself was not instantaneous. Rather, there were waves of conversions that ultimately led to the complete conversion of most of Egypt’s population. These conversions represented an important theme in Egypt’s history, and their impact changed the course of the country. Understanding the history of religious conversions in Egypt is therefore vital to understanding the country itself.

Prior to the Arab conquest, Egypt was part of the Eastern Roman Empire, or the Byzantine Empire. The official religion was Christianity; thus, most Egyptians were Christians. The Arab conquest brought about a lot of change with it, from administrative to cultural and religious.

Accordingly, Islam became the official religion of the state. The conquest also manifested in several varying types of religious conversions, both from one sect to another and from one religion to another. This essay seeks to examine the waves of religious conversions that occurred in Egypt after the Arab conquest of the 7th century. Additionally, this essay will explore the debates that exist within academia on the subject of Egypt’s conversion and the challenges that are faced within the field.

To begin to understand the history of religious conversions in Egypt, one should analyze the country’s political context on the eve of the Arab conquest. Egypt was ruled by the Eastern Roman Empire, later called the Byzantine Empire, for over 600 years at the time of the Arab conquest. During this period, the Romans adopted Christianity as the official religion of the empire in 313 AD and, in the same century, the empire was split into two – East and West. This long history of subjugation by a formidable Christian Empire paved the way for most Egyptians to become Christian by the end of the 6th century (Mikhail 53).

However, it is important to note that several sects of Christianity were practiced in Egypt at the time, although they existed in discord and proselytized for their respective sects (Mikhail 55-58). The most prominent sects included the pro-Chalcedonians and the anti-Chalcedonians. The Byzantine rulers of Egypt were pro-Chalcedonian while most of the native population of Egypt was not, which would come to play an important factor in the development of the early conversions.

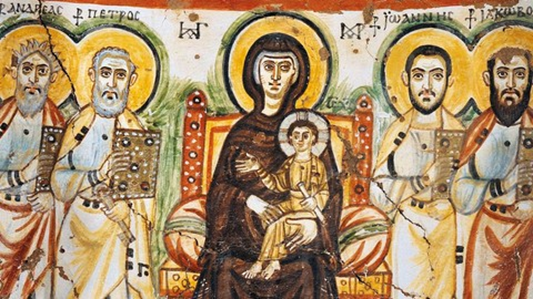

Wall painting of the martyrdom of saints, Coptic period via smarthistory.org

The Arab conquest of Egypt meant a new authority began ruling a country with a distinctly different religion. While the Byzantines and Egyptians were both Christian, they were not of the same sect, so many Egyptians were forced to convert under Byzantine rule. Unlike the Byzantines, the early Arab conquerors did not force conversion on local people and allowed them to continue practicing their own religions. However, the local population was not equal to the Arab conquerors, and they were forced to pay a poll tax, called jizya, in exchange for the freedom to practice their religion. This arrangement was seen by many anti-Chalcedonians, or Copts, as more merciful than what they had to endure under Byzantium (Juynboll 164). Additionally, the pro-Chalcedonians were supported by the now- bygone Byzantine authorities, forcing them to be seen as conspirators with the enemy.

This led to the first wave of conversions after the arrival of the Muslims; many Greek pro- Chalcedonians converted to Coptic Christianity, leading to the resurgence of the Coptic church as the dominating religious sect in Egypt, and a minority converted to Islam (Mikhail 59-60). Several other influences spurred this wave, including that many wanted to integrate and assimilate into the new order of the country. They also lacked a patriarch and support from Byzantium.

Furthermore, becoming Muslim meant being part of an emerging Empire whose official religion was Islam. Consequently, conversion to Islam unlocked many new opportunities for converts and enhanced their social mobility (Simonsohn 199).

The second wave of conversion was slower and less noticeable, occurring during the end of the Umayyad and early Abbasid periods. This was due to the social stigma that accompanied converts (Mikhail 68-70). Since most of the population was still Christian, converting to Islam was seen as abandoning God in pursuit of earthly pleasures.

This attitude persisted throughout the early Abbasid period; however, it gradually became less apparent. There are many reasons for the de- stigmatization of conversion (Mikhail 71-72). For one, the number of converts was increasing. This, coupled with the influx of Arab Muslim migrants from the Arabian Peninsula, was enough to make a robust community that one could join once they converted. Moreover, an existing tolerant Muslim community that mixed with the Christian locals normalized the existence of the religion and therefore normalized conversion to it. Also, Muslim converts were less likely to be left isolated by their family and community. The coming of the Abbasids additionally aided the de-stigmatization immensely. Their policies were relatively egalitarian and less discriminatory in comparison with the Umayyads, as Abbasid rulers in Egypt treated converts in the same manner as they treated all other Muslims. The stagnation of Coptic religious education has also been credited for contributing to the change in attitudes toward conversion (Mikhail 71-72).

The above-mentioned reasons also paved the way for more conversions to occur in the third wave of religious conversions. Furthermore, the lack of proper Christian education led to individuals seeing both religions in the same light (Mikhail 74).

The two religions already shared many similarities in mythology, codes of ethics, and traditions, so when a Christian Egyptian had to choose one, the decision would most likely be in favor of Islam due to the latter offering many social benefits.

Additionally, further de-stigmatization and normalization of conversion to Islam made it easier to make the decision to convert, thus the Coptic church began losing followers in favor of Islam.

Notably, scholarship regarding religious conversion in Egypt in the early Islamic period is not very rich. As a result, scholars have found it difficult to get ahold of texts or other forms of evidence that comprehensively recorded the process of conversion. The scholarship also finds it difficult to determine the particular reasons that motivated conversions. For instance, many scholars agreed that the poll tax, jizya, was the main reason that drove the first wave of conversions (Frantz-Murphy 323-24). However, later scholars would not give all the credit to the poll tax but would provide other reasons (Simonsohn 200).

The gaps in information do not stop here, more problems arose with the topic of taxation in early Islamic Egypt. Although the available tax records are relatively expansive, taxation seems to have been inconsistent, suggesting that the various regions in Egypt paid different taxes at different times. This was because some of those regions were taken by force, while others were taken by treaties, allowing inconsistent taxes and jurisdictions to be implemented in each region (Anderson 69). Additionally, the Umayyads imposed the jizya on Muslim converts regardless, which might have demotivated other Christians from converting to Islam. Evidently, the financial burden associated with different religions was a minor factor in encouraging conversion in the early caliphate in Egypt. Rather, religions’ sense of community and belonging motivated converts. This sense of community was dominated by the Coptic Church, and Coptic Orthodoxy became the dominant religion in Egypt following the Arab conquest. Another challenge for understanding early conversions is that many of the sources that documented them only came centuries after, mostly during the Abbasid and later periods.

Consequently, the scholars who attempted to quantify these conversions potentially lacked adequate sources for their research as both time and bias obscured the accuracy of their evidence. For example, many Coptic works such as “The Apocalypse of Athanasius” depicted the changes in the lives of Christian Egyptians following the Arab conquest, however, this source has considerably exaggerated the events that it depicted as a way of warning other Copts. As such, such sources should be examined with a critical eye.

Painted niche from the monestary of Saint Apollo at Bawit via National Geographic

A lengthy period of diverse conversion processes followed the Arab conquest of Egypt. There were many differing reasons that encouraged people to convert. and numerous types of conversion – from one sect to another and from one religion to another.

Studying the history of religion is crucial because it offers the converted community in Egypt a new set of principles and identities, which went on to shape their lives and consequently the community that they live in. By understanding the history of religious conversion one can understand the community itself. This field of study could also be used to bridge some of the historical misunderstandings between the followers of the two religions.

Bibliography:

Anderson, J. N. D. “Conversion and the Poll Tax in Early Islam. By Daniel C. DennettJr. Harvard Historical Monograph No. XXII, 1950. Pp. Xi, 136, Including Bibliography and Index. 16s.” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, vol. 83, no. 3–4, Oct. 1951, pp. 220–220. Cambridge University Press,

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0035869X00104952.

Frantz-Murphy, Glayds. “Conversion in Early Islamic Egypt: The Economic Factor.” Muslims and Others in Early Islamic Society, Routledge, 2004.

Juynboll, Gautier H. A., translator. The History of Al–Tabari Vol. 13: The Conquest of Iraq, Southwestern Persia, and Egypt: The Middle Years of ’Umar’s Caliphate

A.D. 636-642/A.H. 15-21. Illustrated edition, State University of New York Press, 1989.

Mikhail, Maged S. A. From Byzantine to Islamic Egypt: Religion, Identity and Politics after the Arab Conquest. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2014.

Simonsohn, Uriel. “Conversion, Exemption, and Manipulation: Social Benefits and Conversion to Islam in Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages.” Medieval Worlds, vol. medieval worlds, Jan. 2017, pp. 196–216. ResearchGate, https://doi.org/10.1553/medievalworlds_no6_2017s196.