An exploration of Ana Lily Amirpour’s genre-defying film

A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night is often referred to as the “first Iranian vampire spaghetti western”. Released in 2014, it premiered at the Sundance Film Festival and was American-Iranian filmmaker Ana Lily Amirpour’s feature film debut. It tells the story of a vampire, referred to as ‘The Girl’, who takes the form of a young woman living in a small Iranian ghost-town called ‘Bad City’. The film’s young protagonist has developed a way to enact a sort of vigilante justice, by drinking the blood of those whose behaviour she deems deserving of punishment, such as men who exploit and subjugate women, particularly sex workers. The specificity of the film seems to reject traditional genre categories, and has been described as ‘a spaghetti western’, ‘a horror film’, and ‘a modern film noir’, exploring elements of each of these genres without feeling tied to any.

The vampire protagonist roams the streets of Bad City looking for victims upon which she can feed. She carefully observes the behaviour of her fellow night-dwellers, choosing to pursue men who abuse women and to scare little boys into treating women well. She also chooses to feed upon the homeless, erroneously confident in her ability to select which lives are more valuable than others. While the depth found in the flawed character and vast interior life of The Girl, as well as many of the film’s plot points, could fall into the realm of feminism, Amirpour shies away from calling A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night a feminist film. She does so because she does not want her work to be confined to fighting misogyny just because she is a woman film director. This raises interesting questions about the double standard between male and female filmmakers and the cinematic concept of feminism as a burden. Inequity in the film industry is still glaringly apparent, with white male directors flooding mainstream cinema, but expecting all female filmmakers to uphold feminist values in their films and frame their work as feminist simply because they are women. As such, women filmmakers are often reduced to their gender in a way that hinders the progress of women in film. Amirpour wants to be seen as an artist not defined by her gender. Although her films are clearly informed by her identity as an American-Iranian woman— for example, she was inspired to write A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night when she picked up a chador on another film set, and enjoyed the idea of a vampire using one as a disguise— by distancing her work from the label of feminist, she demands to be treated as a filmmaker, equal to her male peers. The fact that she distances herself from this label does not mean that A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night is not a feminist film- the title alone immediately evokes an image of a woman walking home in darkness, vulnerable to predators who roam at night. However, the film subverts gender expectations and breaks feminist norms with the revelation that The Girl is the predator, and that wrongdoers— usually men— are in danger of her wrath. This is a role-reversal that creates agency for a character who might otherwise be victimised. Yet Amirpour does not want her gender to define, confine, or minimise her work. In an interview with SciFiNow, Amirpour posed the question: “I wonder if when Tarantino made Kill Bill, did people say he was being a feminist?”.

Treating female characters as worthy of exploration should be the bare minimum, not an exceptional, feminist act.

Something else to consider is whether it is still useful to refer to such films as A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night as feminist. It was written and directed by Amirpour, a woman of colour, and follows a female protagonist exploring her desires, her flaws, her complexities, and her choices. This is standard for male characters in a male-dominated industry, but when will it become normal and not feminist to do so for women? It is true that we have not yet reached a stage where female characters will automatically be afforded the same sense of seriousness, depth and attention as male characters, but by referring to this type of work as feminist, are we marking it as radical, as something worthy of praise, as something that goes the extra mile? Treating female characters as worthy of exploration should be the bare minimum, not an exceptional, feminist act. By equating the earnest inclusion of interesting women in film with feminism, we are indirectly saying that anything less than that is standard, an allusion Amirpour is rightly sceptical of. There are obviously potential feminist readings of A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night, but the same could be said for Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining or Roman Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby, and these men are certainly not labelled as feminist filmmakers, nor are they confined to the standard of feminist filmmaking. This is particularly apparent amidst the allegations of their abuse against women which have surfaced in recent years. On the contrary, these male directors have been seen as great artists, free to pursue artistic filmmaking without constraint. Female filmmakers, on the other hand, are often expected to pursue a certain type of cinema, with a certain type of lens.

Having said that, there are interesting points to be made about the political nature of A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night. In a subtle yet highly intentional move, Amirpour includes a fascinating character called ‘Rockabilly’ in several scenes of the film. Always silent, this visibly queer character grabs the attention of the lingering camera, particularly in one scene where Rockabilly appears alone, performing an emotionally-charged, solitary dance. This is a timely and politically-pertinent depiction of the difficulties faced by gay people in Iran. For example, I write this article in the wake of the murder of Alireza Fazeli Monfared, a gay Iranian man who was beheaded by his family members due to his sexual orientation. The story was heard globally, but according to Iranian gay rights activist group 6rang, such an occurence in not uncommon. The manner in which the Iranian government uses Islamic principles in its legislation translates into the criminalisation of consensual, same-sex conduct. Penalties range from flogging to death sentences, but at the same time, the government often permits and sometimes even encourages gender-affirming surgeries, which can sometimes be used to ‘cure’ cis queer people in Iran. Although Rockabilly is relegated to the sidelines, not permitted to speak, their omnipresence throughout A Girl Walks Home Alone At Night pays heed to Amirpour’s opposition to the discriminatory LBGT+ policies espoused by the Iranian government.

She challenges the feminist label assigned to A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night, encouraging us to reflect on why we jump to call stories about women feminist.

Often compared to the likes of Quentin Tarantino, Jim Jarmusch and David Lynch, Amirpour created in A Girl Walks Home Alone At Night a beautiful, stylish, successful film, through which she invites us to be more intentional with our words and our actions. She challenges the feminist label assigned to A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night, encouraging us to reflect on why we jump to call stories about women feminist. Her film defies genre, and her politics defy the status quo, making her one of the great emerging filmmakers of our time.

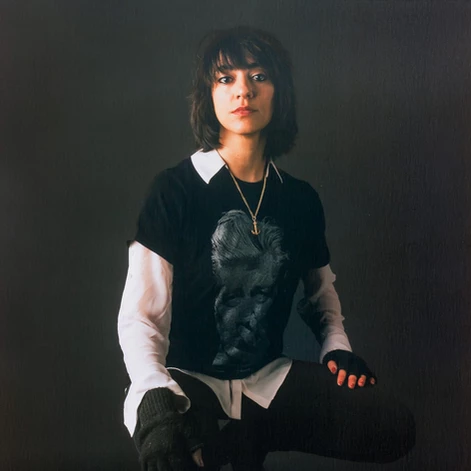

Image Reference

Figure 1: Ana Lily Amirpour – Myrna Suarez, https://www.criterion.com/current/top-10-lists/247-ana-lily-amirpour-s-top-10

Figure 2: https://www2.bfi.org.uk/news-opinion/sight-sound-magazine/reviews-recommendations/film-week-girl-walks-home-alone-night

Figure 3: https://monsterattheendofthedream.com/tag/a-girl-walks-home-alone-at-night-on-netflix-instant/