Beatrica Pistola

Woman at Point Zero is a novel written by Nawal El Saadawi published originally in Beirut in Arabic in 1973. This novel is based on the author’s meeting with Firdaus, a female poisoner in the Qanatir Prison before her execution. This first person’s account of the prisoner’s life explores, through Firdaus’ experiences, the role of women in the patriarchal society of Cairo and their oppression. She described it to be ‘more or less a real story with some imagination’ (El Saadawi 1992). At the time, after being fired as both the Editor in Chief of the magazine Health, which was closed down due to political pressure, and the Director of Health education, Saadawi was conducting her research on Neurosis in Egyptian women (Cooke M. VI). This is when, through the prison doctor, she found out about Firdaus and after several failed attempts, she managed to meet her and interview her (Cooke M. VII). The book, like most works by Saadawi, was banned in Egypt because of the ongoing tension between the author and the government following the attempted publication of Women and Sex in 1969, where she openly criticised the widespread practice of female circumcision in Egypt and ‘society’s fixation with virginity’ (Cooke, R.).

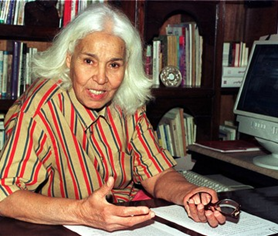

Nawal El Saadawi is one of the most influential feminist intellectuals in the Arab world as well as an advocate for women’s rights both in Egypt, her country of origin, and abroad. In 1982 she founded the ‘Arab Women’s Solidarity Association’, which was outlawed less than a decade later, in 1991 (Cooke M. VI). Living part of her life in exile, Saadawi taught in universities in both Europe and the United States before going back to Egypt in 1996. In 2004 she presented her campaign as a candidate for the Egyptian presidential elections, advocating for human rights, greater freedom and democracy (Cooke M. VI). However, just one year later, she was forced to withdraw her candidacy due to political instability and government persecution. After winning several prizes and receiving numerous honorary degrees from universities throughout the world, she died in 2021 in a hospital in Cairo (Cooke M. VII).

Saadawi defined herself as a social-feminist and, as an anti-capitalist, did not believe that the feminist struggle can be won under a capitalist system, which she believed was where the root of women’s oppression lies (Fariborz). In terms of the influence of religion on Egypt and on the role of women in the country, Saadawi was of the opinion that “the root of the oppression of women lies in the global post-modern capitalist system, which is supported by religious fundamentalism” (Fariborz). Therefore, although Islam plays a part in supporting the patriarchal system in place, the oppression of women in the context of Egypt cannot entirely be traced back to religion. The roots of the patriarchal society presented in Woman at Point Zero seem to go beyond Islamic fundamentalism, which was not as popular at the time of Firdaus’ childhood. In the book, the author is critical of the use of religion as a discourse to justify the oppression of women, but does not situate this problem in Islamism but rather in a societal structure that originates from before. For the author, religion was a private matter and its politicisation did not benefit society in a wider sense because religion should not be used as a discourse to gain political power (Akkawi). She was against fundamentalism of any kind, whether Christian, Jewish or Islamic, as she believed women were the first targets of oppression in their political agendas (Akkawi). Furthermore, she considered the use of the veil as a tool of oppression for Muslim women in political discourses (Nassef). She strongly opposed the Muslim Brotherhood and described them as both backwards and reactionary, harmful to Egyptian politics and society (Etezadosaltaneh and Kabir).

The time of publication of this novel is attributed particular importance because the 1970s, after the loss of the Six-Day War against Israel in 1967, saw the rise of conservatism and religiosity throughout the Middle East. Before these events, Egypt, ruled firstly by Nasser and then by Sadat, saw the separation between religious institution and state, in an attempt to modernise the country.

IThe 1967 defeat opened the doors for new intellectual thoughts and activism which aimed to criticise Arab societies in an attempt to address and explain the failure. This is reflected in Woman at Point Zero’s revolutionary tone and its aim to challenge the essence of Egyptian society by breaking down its faulted structure through the life experiences of Firdaus.

Via Reuters

Nawal El Saadawi, a revolutionist since birth, was highly critical of the corruption of religious systems and the role they played in the oppression of women. Rather than being critical of Islam itself, she was concerned with the institutions built around it, such as Al-Azhar, which she (Note 1) considered a ‘dangerous reactionary force’ (Akkawi)

. According to the author, this institution, by censoring studies and books and choosing not to educate the youth on important themes such as rape and gender inequality (Note 2), was controlling the religious discourse (Akkawi). Saadawi’s secular socialism, which advocated for the separation of religion and state, and her fight for the alleviation of women’s oppression can be considered incompatible with the rise of the Muslim Brotherhood, who advocated for strict rules on female dressing, change of the school curriculum for girls and thorough instruction on topics considered “proper” for a woman (Freer). Saadawi believed that gender and class divisions, as well as religious fundamentalism increased corruption in Egyptian society (Cooke, R.). Children who were born in lower class families did not have the possibility to progress in their career, promoting the stagnation of society. With the increase in gender division, even educated women would often end up working at home while trapped in an arranged marriage or dedicating their lives to prostitution (Cooke, R.).

This is reflected in Woman at Point Zero, where Firdaus’ secondary school diploma was not valued because of her gender and since her uncle refused to send her to university, her only options were to either stay in her arranged marriage or find a way to make a living by herself, a difficult task in the patriarchal society she was living in. However, even though the Muslim Brotherhood believed in the merging of religion and state, which went against Saadawi’s political stance, the modernisation project at the time of Nasser and Sadat came with increased censorship and banned most of Saadawi’s books and other publications (Fariborz). Therefore, if her work and similar projects by other authors were banned, it can be said that the project for modernisation in place before 1967, through an intellectual scope, did not grant freedom of speech and did not encourage the education of the population on certain topics. If modernity had not failed in terms of infrastructures and economy, the government had failed to modernise the society, explaining Firdaus’ incapability to escape the patriarchal system she seems to be trapped in. Therefore, the project for modernity can be said to have failed long before the rise of Islamism in the context of Egypt.

This book, reflecting Saadawi’s role as a radical feminist, places every man, with no exception, into a patriarchal framework whereby he is given the right to abuse, both emotionally and physically, the protagonist. The novel aims to show that all men are equally implicated in the framework, all the way from her childhood, with her father, to her imprisonment, with her pimp. This framework is entirely created by men, who, being in positions of power, are given the right to trap women into a system that automatically subjugates them to men. Certain female characters, such as Sharif, Firdaus’ uncle’s wife and her mother, are also recruited in this patriarchal system of oppression, leading to the ideological notion that choices made by women are not necessarily feminist choices.

Woman at Point Zero aims to show how certain female characters perpetuate the patriarchy in an attempt to oppress one another . This comes from their internalisation of stereotypes that have been constructed and imposed upon them by men (Note 3). Even the women that are not recruited in the patriarchal system do not show powerful solidarity, with the exception of the protagonist’s teacher in school. This framework places the victim, in this case Firdaus, in a position of fear, used as a justification as to why she has never stabbed a man before. Moreover, the rooted misogyny of Egyptian society, which attributes little importance to women’s discourses and fosters the protagonist’s passivity towards her own life events. What makes this novel particularly revolutionary is that it is not limited to narrate Firdaus’ life story, but it rather aims to criticise Egyptian society as a whole. Firdaus could be any woman and her master could be any man, they serve as representatives of their respective genders . Due to the symbolic nature of her role, Firdaus is therefore a martyr for Egyptian women upon her death. The uncompromising behaviour of the protagonist, which eventually led to her execution, is the only radically feminist possible outcome to this patriarchal system Egyptian women are trapped in. Asking Firdaus to apologise for the killing of a man is forcing her to submit to the system, but she chose freedom. This book encourages women all throughout the world to resist, rather than coexist, with the patriarchal system imposed upon them.

By identifying religion as a facilitator for the oppression of Arab women and the breaches of human rights, Saadawi did not believe in the coexistence and compatibility of the two in any Arab society (Akkawi). As explored throughout the book by analysing the events of Firdaus’ life, the most pious men, also part of the patriarchal system in place, use religion as a justification for the oppression of women and gender based violence.

Moreover, when Firdaus rushed to her uncle’s wife after being physically assaulted by her husband, her aunt, who is also rooted in the patriarchal system, reassured her by saying that ‘it was precisely men well versed in their religion who beat their wives. The precepts of religion permitted such punishment’ (Saadawi 59). Additionally, it appears by reading the novel that Islam sets an

expectation for the behaviour of women which often leads to their oppression, promoting notions concerning women’s obedience to men, with disobedience often leading to rape and other punishments. Woman at Point Zero also criticises the institution of Islamic marriage, which is described as ‘the system built on the most cruel suffering for women’ (Saadawi 118). As proven by both Woman at Point Zero and her book The Fall of the Imam, she is very critical of corruption in Arab societies and considers the interconnection of politics and religion to be one of its main causes (Akkawi). Woman at Point Zero, however, should not be interpreted as a window into the timeless nature of the Islamic religion but instead as a series of events which need to be placed into their respective historical contexts (Balaa 243) (Note 4). This distinction is important, because it shows that the novel does not intend to criticise Islam, as believed by Islamists, but to rather explore how it has been used as a discourse to facilitate the patriarchal system, contrary to the Arab widespread perspective on Nawal El Saadawi, who is locally believed to write for the West (Fariborz; Balaa 236- 253) (Note 5).

While it is true that the novel plays into some Western Orientalist stereotypes of the region, it also challenges others (Balaa 250). For instance, Firdaus does not reflect the Orientalist stereotype of the silent and obedient Muslim woman that is often marginalised both in real life and as a character in other Arab intellectuals’ novels. The protagonist of the novel is a woman, and her life events are central to the narrative. The publication of this novel, as well as Firdaus’ agreement to speak to Saadawi, are themselves acts that aim to challenge the patriarchal system and authoritarian political structures of Egyptian society. Woman at Point Zero gives voice to the voiceless and space to the marginalised.

Overall, it can be said that Woman at Point Zero by Nawal El Saadawi perfectly reflects the radically feminist nature of the author and her concerns with the politics of the time. By telling the story of Firdaus, Saadawi managed to critique Egyptian society and the role of religion in promoting the patriarchal framework that men and women are part of. According to the novelist, religion was often used to justify the segregation and oppression of women, proven in the book by Firdaus’ aunt’s reaction when she came home looking for help after her husband abused her. Moreover, the author goes on to criticise the institution of the Islamic marriage and the corruption in Arab societies, which, as stated in various interviews, she believes to be encouraged by fundamentalist ideologies (Akkawi).

Her work is highly criticised as it is said to fuel the Western Orientalist narratives on the Middle East and Islamic religion, but after a deeper analysis, it is clear the author is trying to break stereotypes (Balaa 236). Firdaus challenges the patriarchal system rather than subduing to it and by accepting the death penalty rather than apologising for the killing of a man she becomes a martyr for women in Egypt. The book does not aim to explore the timeless nature of Islam but it rather tries to show how religion has been used as a discourse to oppose change (Balaa 240). Even though the author believed that Islamic fundamentalism worsened the condition of women, the problem is considered structural rather than dependent on the rise of Islamism (Fariborz). This book, published in 1973, explores the life of a woman who was born long before the rise of Islamism after 1967, but who was still unable to escape Egyptian patriarchal structure. This problem can be attributed to different factors including the lack of freedom of speech during Nasser and Sadat, which prevented people from being informed in regards to important societal and intellectual issues (Fariborz). Therefore, even though Islamic values were used as a justification for the oppression of women, the structural issues which prevented modernisation originated from before and cannot be attributed entirely to Islamic fundamentalism.

Note 1: Although the author was not critical of Islam itself, she did not agree with the restrictions on critiquing religion that were imposed in Egypt because built around anti-liberal notions which promoted censorship (Akkawi 2021).

Note 2: While the power of this institution was suppressed during Nasser’s rule, they were still very influential in censorship and religious education

Note 3: Nawal El Saadawi admitted in an interview that she considered Sadat’s wife a woman against women because of her work against women rights within Egypt and her participation in the fragmentation of the local feminist movement. According to the author, Sadat and his wife advocated for the separation of women, classes and religions, which is what led to religious fundamentalism. Therefore, these characters from Woman at Point Zero play a similar role to Sadat’s wife in the patriarchal framework (Cooke, R. 2015). Firdaus’ uncle did not agree to let her study in university because a ‘man of religion’ would not let his niece spend time in the company of men.

Note 4: The author believed President Sadat to have greatly contributed to the widespread corruption in Egypt (Cooke, R. 2015).

Note 5: This, according to the author, is because her work is censored in Egypt and the majority of the Arab World, meaning that Western media outlets are the only platforms that offer her complete freedom of speech. In Egypt, she has barely been able to speak on national television or write articles for the national newspaper, her work is limited to the small opposition newspaper, explaining why she gained more visibility outside of her country of origin (Cooke, R. 2015).

Bibliography:

Akkawi, Hala. “An Introduction to Nawal El-Saadawi’s Controversial Views on Religion, Politics, Women, and Death.” WatchDogs Gazette, 6 April, 2021.

Balaa, Luma. “El Saadawi Does Not Orientalize the Other in Woman at Point Zero.” Journal of International Women’s Studies, vol. 19, no. 6, 2018, pp. 236-253.

Cooke, Miriam. Foreword. Woman at Point Zero by Nawal El Saadawi. ZED Books, 2015 pp. VII-VIII.

Cooke, Rachel. “Nawal El Saadawi:‘Do You Feel You Are Liberated? I Feel I Am Not.’ The Guardian, 11 October 2015. El Saadawi, Nawal. Woman at Point Zero. Translated by Sherif Hetata. Zed Books, 2015.

Fariborz, Arian. “Interview with Nawal El Saadawi.” Translated by Jennifer Taylor. Qantara, 2014.

Etezadosaltaneh, Nozhan and Kabir, Arafat. “Q&A with Nawal El Saadawi.” International Policy Digest, 2 March, 2014.

Freer, Courtney. “The Influence of Islamist Rhetoric on Women’s Rights.” London School of Economics Middle East Centre, 20 December 2017. Johnson, Angela. “Interview: Speaking at Point Zero: Talks with Nawal El-Saadawi.” Off Our Backs vol. 22, no. 3, March 1992 pp. 1-7.

Nassef, Ahmed. “EGYPT: El Saadawi: ‘The veil is a political symbol’.” Greenleft, Issue 574, 17 November 1993.

Smith, Sarah. “Nawal El Saadawi Obituary.” The Guardian, 22 March, 2021.