Luther (Louie) Lyons

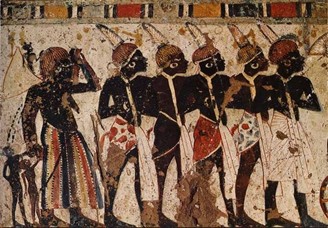

Perhaps one of the more significant gaps in any ‘layman’s perspective’ is the debate about the representation and cultural imagery of Ancient Egyptians that is strongly disposed to depict them as Europeanised white. African scholars from Cheikh Anta Diop to Okot P’Bitek, and other Afrocentrists since the writings of John Henrik Clarke and Chancellor Williams, argue that this misrepresentation of Ancient Egyptians has been perpetuated by a Eurocentric academy.

Attempts to prove that Cleopatra or Tutankhamen were black have been met with fierce academic opposition in the West and continue to be contested by mainstream academia.

However, for our nominal layman, the real issue here is that this contested blackness as part of an Ancient Egyptian identity overshadows the fact that Egypt’s unquestionably black figures, such as the pharaohs of the 25th Dynasty, are frequently missing in the visual representation of the racial identity of Egypt’s dynasties. Similarly, the extent of migration and co-mingling between Egypt and Nubia has failed to make any impact on a lay understanding of the complexity of Egypt’s ruling dynasties. This is a significant element in the general misrepresentation of Egypt as an Ancient Near Eastern or Mediterranean civilisation, which negates its positioning as an African one.

Egypt in the West and Egyptomania

Egyptomania in the West came into its own with the Napoleonic campaign and Champollion’s subsequent translation of the Rosetta Stone. The level of recognition of certain Egyptian figures began to grow, especially those from the New Kingdom about whom we have much information. The discovery of Tutankhamun’s burial tomb played a significant role in engendering the popularity of Egypt and Egyptology from the 1920s onwards, and “Tut-mania” is invoked whenever Egyptian artefacts arrive in a museum. Ironically, this Egyptomania has preserved the legacies of Hatshepsut, Nefertiti, and Akhenaten, whom the Egyptians wished to erase.

The prosperity of Egypt in the New Kingdom is undeniable and because of this Ramesses the Great, in particular, was able to engage in a considerable number of building projects.

Ramesses the Great’s prominence in the biblical story of Moses immortalised him in the annals of history. He is often considered the greatest and most distinguished Pharaoh, reaching such a level of renown beyond many other ancient Middle Eastern figures. He has captured the imagination of a wide range of artists throughout the years including inspiring a poem by Percy Bysshe Shelley and inspiring a character for both DC and Marvel Comics. The New Kingdom is often seen as the pinnacle of Egyptian power. Consequently, it is appropriate to concede the importance of this period in ancient Egyptian history and understand why this period is the exalted among many Egyptologists and therefore preeminent in the public imagination. However, if the basis for the flood of New Kingdom representation in modern media is its prosperity, stability, construction of monuments, a discovery of a royal burial site, a reference in the bible, and a canon of inimitable pharaohs are the requirements for recognition amongst the general public then it is a wonder the era of the 25th Dynasty is not more renowned as it too contained all of these.

The Black Pharaohs

The reign of the black pharaohs saw many of the staples of a quintessentially successful dynasty – a king who unified both the North and South, an increase in the construction of monuments, a successful defence of Egypt against the Assyrians in 674 BCE, and a dedication to ma’at. The 25th dynasty started with the Nubian king, Piye, who campaigned successfully in an Egypt fractured after the Third Intermediate Period. Piye commemorated his success in a stele that demonstrates his view of this conflict as a holy war to return “proper” Egyptian culture to Egypt, demonstrating in an explicit manner the connection between Egypt and Nubia, whereby the Nubians were viewed as true champions of Egyptian culture. It was in the reign of one of his successors, Shabaka, that the Delta was conquered and Egypt was unified.

Building upon this, Taharqa continued Piye’s restoration of Egyptian culture by returning Egypt to pyramid building, greatly increasing the number of building projects, although much of his construction occurred near the third and fourth cataracts. Taharqa built a new temple at Kawa and built the largest Nubian pyramid in Nuri which became a necropolis for Kushite kings.

Additionally, Taharqa added to the temple at Karnak and is featured in the bible. This brief section of history where Nubia retained control in their relationship with Egypt was brought to an end when the Assyrians conquered Egypt in 671 BCE.

Nubia and Egypt

The cultural renaissance of the 25th Dynasty was undeniably impactful but was certainly not the extent of cultural relationship between Egypt and Nubia. The two kingdoms enjoyed a long relationship with much cultural exchange, exogamy, and trade. While the two lands were distinct, Nubia was undoubtedly “Egyptianised” throughout much of its history but where the gap in the layman’s perspective is that the cultural exchange went in both directions.

Many Nubians entered Egypt as mercenaries and a major addition to the Egyptian army was the presence of Nubian archers. An example of this migration and assimilation is Mahirper, a Nubian who became a key advisor during the New Kingdom, likely for Thutmose IV. Nubian rulers were said to have employed many Egyptians as well. Nubia also contained greater deposits of gold, silver, and electrum than Egypt. This cemented Nubia’s importance to Egypt, at times as a vassal state during the New Kingdom but also as a trading partner as far back as the 6th Dynasty.

The Hamitic Hypothesis

If Nubia was an accepted part of Egyptian culture, whether with a golden age of its own or as part of the ruling class of Egypt, and given the modern public’s fascination with Ancient Egypt, why has the Nubian element of Egyptian society failed to be spark the engagement of the person in the street? Elements such as a lack of understanding of Cushitic language and the First and Second Sudanese Civil Wars making archaeological excavations in the region more difficult may be identified as factors which have impinged on academic engagement with this topic. However, another potential explanation may lie with the Hamitic Hypothesis.

The Hamitic Hypothesis was a theory of biological racism based on the biblical story of Noah and his son, Ham. This hypothesised that Ancient Egyptians and their descendants, positioned as white, had ruled large parts of Africa and that they were responsible for any major achievement within the continent, especially within Black sub-Saharan regions, the implication being that the Indigenous people were incapable of such feats. Thus white Europeans found a mechanism to balance their racialisation of the black African with their 19th century discoveries of the inarguable ingenuity of ancient African art and structures such as Great Zimbabwe. Napoleon’s conquest of Egypt and the introduction of Egyptian art to Europe resulted in the exacerbation of this hypothesis, and the Eurocentric severing of Egypt and Africa. This conceptualisation framed the Egyptians as being on a level above the black African, creating an ‘otherness’ between Egypt and Africa. Egypt became a central point of contention in the argument for slavery in 19th century America. This resulted in claims as early as 1844, when George Gliddon claimed that Egyptians had an Asiatic origin and “Egyptians were white men, of no darker hue than a pure Arab, a Jew, or a Phoenician”, thus obviating any African heritage.

Egyptian monuments and achievements were lauded as the success of white Egyptians, with Nubians being relegated, in Samuel Morton’s words, to “servants and slaves”. This conceptualisation of Egypt no longer allowed for the existence of the accomplishments of the Nubian Empire, let alone full recognition of a black Nubian dynasty ruling over Egypt.

Conclusion

This lay perspective of an Egyptian civilisation as explicitly non-African has permitted the pictorial characterisation of the Ancient Egyptian as white to endure. While the Grecian origins of Cleopatra may allow for her representation by Elizabeth Taylor or Gal Gadot, the exclusion of black Nubians from our idea of Egypt may be because the Nubian pharaohs underwent a campaign of revisionism in the 19th century to strip them of either their achievements, with claims that caucasian Egyptians had built their monuments, or their race, when Karl Richard Lepsius used the artwork of Ancient Greece to claim the Nubians themselves were Caucasian. Either way, the Nubian component of Egyptian history continues to be underrepresented and has doubtlessly failed to make its due mark in the mind of the layman.

Asante, Molefi K. “African ways of knowing and cognitive faculties.” Encyclopedia of Black Studies. Thousand Oaks: SAGE (2005). Asante, Molefi Kete. An Afrocentric Manifesto: Toward an African Renaissance. Polity, 2007.

Baum, Bruce. The rise and fall of the Caucasian race: A political history of racial identity. NYU Press, 2006.

Charles Rivers Editors. The Foreign Invaders of Ancient Egypt: The History of the Hyksos, Sea Peoples, Nubians, Babylonians, and Assyrians. Charles Rivers Editors (2016).

Diop, Cheikh Anta, and Mercer Cook. The African origin of civilization: Myth or reality. Chicago Review Press, 2012.

King James Bible. Exodus 12:37. Available at: https://www.kingjamesbibleonline.org/Exodus–12–37/. (Accessed: 5 January 2022).

Gliddon, George Robins. Ancient Egypt: Her monuments, hieroglyphics, history and archæology, and other subjects connected with hieroglyphical literature. W. Taylor, 1847.

Hoffmeier, James K. Akhenaten and the Origins of Monotheism. Oxford University Press, 2015.

Kendall, Timothy. “Racism and the Rediscovery of Ancient Nubia.” Black Kingdoms of the Nile. PBS. Accessed December 26, 2021. https://www.amazon.com/Foreign- Invaders-Ancient-Egypt-Babylonians/dp/1539857336.

László, Török. (1997). The Kingdom of Kush Handbook of the Napatan-Meroitic Civilization. Leiden: Brill.

Lefkowitz, Mary. Not Out Of Africa: How”” Afrocentrism”” Became An Excuse To Teach Myth As History. Basic Books, 2008.

Lepsius, Carl Richard. “Denkmäler aus Aegypten und Aethiopien: nach den Zeichnungen der… 1842-1845 ausgeführten wissenschaftlichen Expedition.” (1849). MacDonald, J. (2018). The Lost Kingdom of Kush. Available at: https://daily.jstor.org/the-lost-kingdom-of-kush/. (Accessed: 23 December 2021).

Malamud, M. (2016). African Americans and the classics: antiquity, abolition and activism. London, New York: I.B. Tauris.

Malik, H. (2011). The Forgotten Kingdom of Nubia: What is the Message of the Nubian? Available at: https://www.thenubianmessage.com/2011/09/28/the-forgotten- kingdom-of-nubia-what-is-the-message-of-the-nubian/. (Accessed: 23 December 2021).

McAlister, Melani. “” The Common Heritage of Mankind”: Race, Nation, and Masculinity in the King Tut Exhibit.” Representations 54 (1996): 80-103. Meyerson, Daniel. The Linguist and the Emperor: Napoleon and Champollion’s quest to decipher the Rosetta Stone. Random House Incorporated, 2005. Mukhtār, Muḥammad Jamāl al-Dīn. UNESCO General History of Africa, Vol. II, Abridged Edition: Ancient Africa. Vol. 2. Univ of California Press, 1990.

Molinero, Manuel Angel. “Napoleon‘s Military Defeat in Egypt Yielded a Victory for History.” National Geographic, January 18, 2021. https://www.nationalgeographic.co.uk/history-and-civilisation/2021/01/napoleons-military-defeat-in-egypt-yielded-a-victory-for-history. O‘Connor, David B. Ancient Nubia: Egypt‘s Rival in Africa. University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology & Anthropology, 1993.

Putnam, James. Egyptology: An Introduction to the History, Art, and Culture of Ancient Egypt. Crescent, 1990. Redford, Donald B. From slave to pharaoh: the black experience of ancient Egypt. JHU Press, 2004.

Rilly, Claude, and Alex dE Voogt. The Meroitic language and writing system. Cambridge University Press, 2012. Rogers, Joel A. “World‘s Greatest Men of Color.“ New York: MacMiillian (1946).

Sanders, Edith R. “The hamitic hyopthesis; its origin and functions in time perspecive1.“ The Journal of African History 10, no. 4 (1969): 521–532. Shaw, Ian, ed. The Oxford history of ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press, 2003.

Tyldesley, Joyce. “Hatshepsut and Tuthmosis: A Royal Feud? .” BBC History, 2011. Accessed December 18, 2021. https://history–files.blogspot.com/2013/10/hatshepsut– and-tuthmosis-royal-feud-by.html.

Welsby, Derek A. The Kingdom of Kush. The Napatan and Meroitic Empires. British Museum Press, 2002.

Williams, Chancellor. The destruction of Black civilization: Great issues of a race from 4500 BC to 2000 AD. Third World Press, 1987. Wolfman, Marv. “Fantastic Four Annual Vol 1 #12.” New York, New York: Marvel Comics, 1977.